Published 5th March 2024

500 public pools may close without strategic investment

Millions of Australians visited a local community swimming pool over summer, but new research shows that as many as 500 will close within 10 years without significant and sustained investment.

Royal Life Saving research estimates that 68% of community swimming pools are aged over 50 years, and that $8 billion is needed to refurbish, upgrade, or rebuild them.

Royal Life Saving research highlights:

- The average Australian public pool was built in 1968

- 500 (40%) of public pools will reach the end of their functional lifespan by 2030

- $8 billion is needed to replace those 500 aging public pools

- A further $3 billion will be needed to replace facilities ending their lifespan by 2035

- Pools generate $9.1 billion annually in social, health, and economic benefits

- There are over 333 million visits to public pools each year

- Every visit to a public pool generates $26 in health system savings

Sadly, many community pools are facing multiple threats - changing demographics, lack of local government resources, increasing energy and building costs, the impacts of a changing climate.

Royal Life Saving’s RJ Houston, General Manager – Capability & Industry, emphasised the critical state of the nation's aquatic facilities. “It is much more than rusted and broken pipes, cracks in pool tiles, and porous concrete, many older pools are leaking significant amounts of water, leading to increased costs, environmental damage and concerns about water quality and safety.”

Local government shoulders the greatest burden, many are now unable to meet the upgrade costs without financial assistance from State and Federal governments.

Research shows that local governments contribute 64% of all funding. Regional councils are particularly vulnerable and often face the dilemma of pool closures.

“Without a more structured approach to swimming pool investment, more children will miss out on swimming lessons, communities won’t have a safe place to swim laps or cool off during summer, and many will be forced to swim in rivers, and lakes,” Mr Houston said.

Communities are forced into a complex web of grants. Securing funds is more challenging for those in regional and outer metropolitan areas.

Communities are often paralysed by competing agendas – laps versus lessons, families versus the needs of an ageing population. The system creates winners and losers.

This lack of a cohesive framework opens the door to suboptimal decision-making, depriving some communities of access to safe swimming facilities and essential water safety skills.

Royal Life Saving advocates for a strategic, long-term solution.

“The benefits of public pools are clear, and decisive leadership is needed. There is a strong case for an investment fund dedicated to aquatic facility upgrades and new builds. Public funds should be allocated to function over form and aim to ensure communities maximise health and social benefits,” Mr Houston said.

Regional and metropolitan community needs analysis are needed to forecast the short, medium, and long terms needs. Funds should be made available for feasibility and planning stages to ensure that projects are shovel ready, carefully considered and in line with community needs.

Royal Life Saving proposes five principles for investment in swimming pool infrastructure:

- Provide funds to support regional and metropolitan area gap analysis

- Provide funds to support feasibility and fit-for-purpose studies early in process

- Target and plan funding for refurbishments and new builds in growing areas

- Prioritise functionality and community need over aesthetics and interest groups

- Link development funds to established health and social indicators

See also:

- State of Aquatic Facility Infrastructure Report (2022) https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/Aquatic-Risk-and-Guidelines/aquatic-research/the-state-of-aquatic-facility-infrastructure

- Health, Social and Economic Value of the National Aquatic Industry (2021) https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/Aquatic-Risk-and-Guidelines/aquatic-research/Health-Social-and-Economic-Value-of-Aquatic-Industry

- The Social Impact of the National Aquatic Industry (2021) https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/Aquatic-Risk-and-Guidelines/aquatic-research/Social-Impact-of-Aquatic-Industry

- Equal Access to Public Aquatic Facilities (2022) https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/Aquatic-Risk-and-Guidelines/aquatic-research/equal-access-to-public-aquatic-facilities

- Economic Benefits of Australia’s Public Aquatic Facilities (2017) https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/37563/RLS_IndustryBenefits_LR.PDF

- Remote Pools – A review of Swimming Pools in Remote Areas of the Northern Territory https://www.royallifesaving.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/37563/RLS_IndustryBenefits_LR.PDF

Photo: Cessnock Municipal Baths, built 1949

Photo: Horsham War Memorial Pool, built 1955

Photo: Enfield Olympic Pool, built 1940

Photo: Kurri Lurri Pool under construction, circa 1949

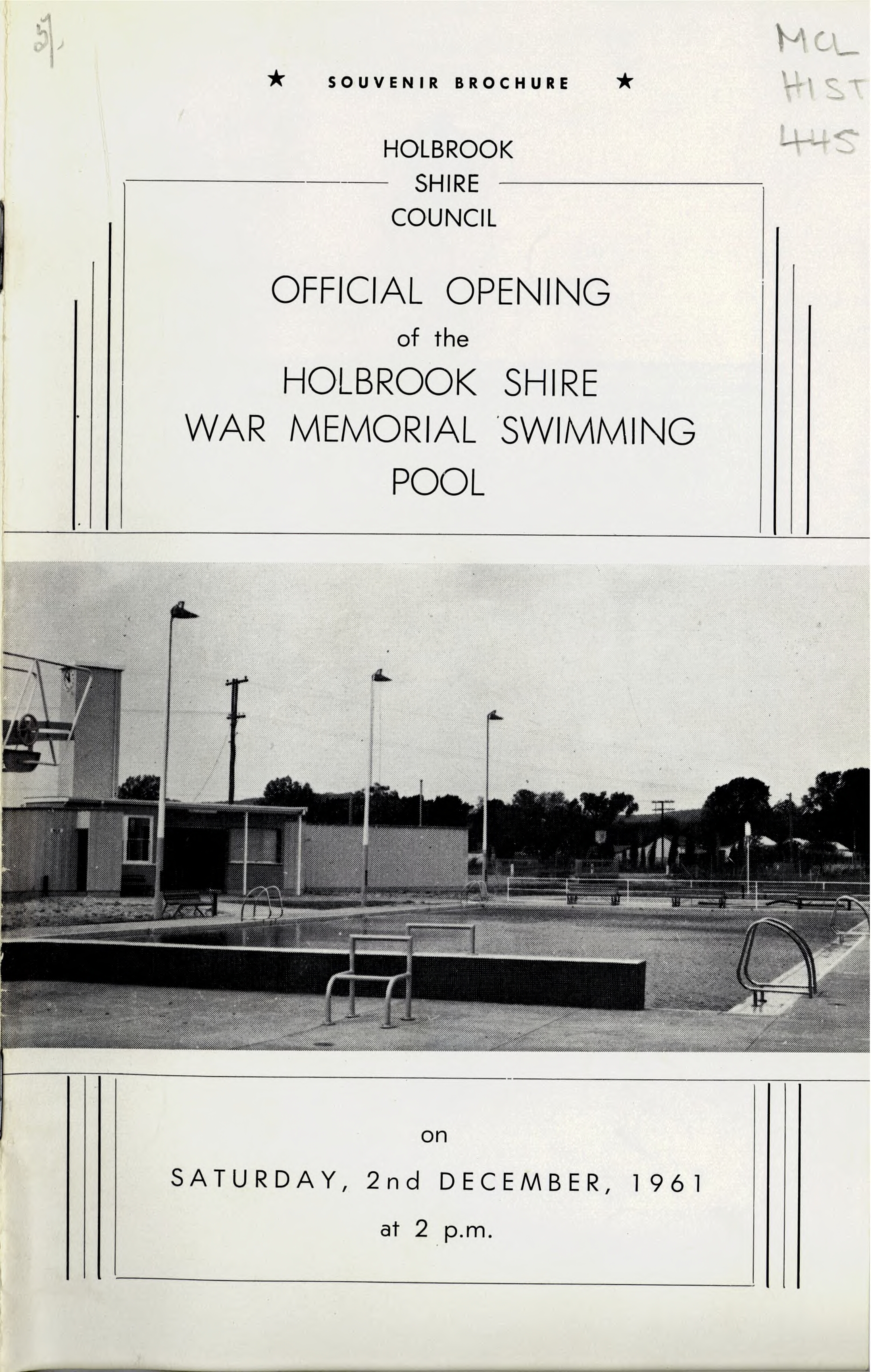

Photo: Holbrook Shire War Memorial Pool, built 1961

Photo: Avenel Swimming Pool, 2024. Pool constructued in 1962.

Photo: Nagambie Pool in 2024, constructed 1969.

Historial images: are courtesy of the National Library of Australia database, available at: https://www.nla.gov.au/

New images courtesy of Bobby Page, Belgravia Leisure.